A ridiculous satirical story by Isaac-Meyer Dik, which I translated from Yiddish. "The Hullaballoo," aka "The Crisis."

The Hullabaloo

1. The Sorrowful Letter

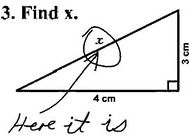

In the year 5594 (1834), on the morning of Tisha-B'av, when the congregation recites the prayer mourning the destruction of the temple, one of the town's greatest householders entered with a letter in hand and went straight to the trustee, the leader of the community, and said to him breathlessly: "Reb Benyomin, I ask you to read this letter quickly, it's no simple thing, it concerns the whole people Israel."

That speech worked on the crowd like a thousand-pound stone falling into a quiet lake.

And it happened that the trustee read through the letter, burst into tears, wrung his hands, tore his clothes, pulled the hair from his head and shouted: "A misfortune, a great misfortune has befallen us!"

And the people in shul became so frightened that the saying of prayers flew right out of their heads. They turned their glance to the important personage who had brought the letter, and to the trustee, wanting to understand how far this misfortune would extend.

It was, however, impossible to guess. People hurried through the prayer as one does through the second half of the siddur on the second night of Passover, and slipped out into the street. There were soon consultations in progress around every house. One person whispered in another's ear, and nobody really knew what had happened.

2. The Big Meeting

And it happened that while all the people were standing around in little clusters, racking their brains over what new kind of evil decree this might be, the town's sextons were seen running from house to house calling everyone to the rav for a meeting.

First the rav's assistants were called, the greatest scholars. The distinguished householders were called next, and afterwards, the simple folk too, and even those who were total paupers. The only ones left at home were a few who were sitting shiva.

And when all had gathered together at the rav's, the door was locked and the trustee stood before the assembly and spoke on behalf of the rav, who wasn't feeling well. "Let it be known, at any moment it may occur, an evil decree is abroad which strikes straight at the heart. A directive which will affect not just one simple commandment, but the entire survival of our people. It says that no Jewish daughter may be married before the age of sixteen, and no youth before he is eighteen years old. Understand, dear brothers, this is a worse decree than Pharoah's, because his was directed only against boys and this one strikes at us all..."

And he read them the letter he'd received. It had been written by one of his in-laws in the capitol; this in-law had written to him about the secret of the new edict so he could be ready and marry off his daughter in time.

The trustee's speech and the letter hit the people so hard, they all began to cry, not one eye was dry! People thought it was the start of the troubles that bring the coming of the Messiah...

For two hours they sat and wondered what to do. Finally it was decided that everyone who was faithful to God and His people Israel should immediately, right now on the Ninth of Av, marry off his son or daughter so that if the edict arrived the next day it would already come too late.

And this would all be done secretly, so that, God forbid, there would be no pitfalls/accidents/untoward outcomes.

3. The Turmoil/Riot/Stampede in Town

But the crowd had barely come away from the meeting when there was already ranting and raving in every house, in the public bath, in the mill and the poorhouse. A couple of tailors who had slipped out of the meeting early told a certain wadding-maker who had been in the street just then; he inflated the story a bit and carried it between the stores. An hour later the business had been told and retold, most people adding a bit from their own imaginations. Half an hour later, allusions to this edict had been found to exist in the old books. And the Khasidim said their rebbe had already known about this situation for a long while and had therefore already married off his little Shmuel in time.

Briefly: as soon as the assembly had left the meeting, the people divided into two groups - one group, shadchns (matchmakers), the other group, in-laws. It was a rainy day, but people ignored that and walked the muddy streets in their socks [are their shoes off for the mourning of the temple?], one person whispered and plotted with another, demonstrating/arguing/showing how suitable this match or that match would be. By nightfall, more than half the town had made engagements.

The first matches were made by poor people whose Rav was a Khasid. The Khasidic Rav was also something of a rabbi - he took rabbi's payments and gave out amulets; he also dealt in prayer shawls. He made a big fuss about the edict among the menfolk and their wives, and the rebitsin raised even more of a to-do among the women, whom the edict had frightened even more than their husbands, because each of them remembered that by the age of sixteen she herself had already been either divorced or living in disharmony with her husband, whereas her daughter at that age would just be beginning.

And barely had the first stars been seen in the sky, folks hadn't yet even had a chance to eat anything, when khupahs were already going up in the houses - quiet weddings, without musicians, without the ritual clown (badkhn), without the ritual veiling and bedecking of the bride. That's what the Rav had ordered - first, because after all it was still Tisha B'Av, and second, so nobody in town would know.

There were so many khupahs that night, it was hard to find ten men to say the blessings at each wedding, and I, who lived near the synagogue courtyard where the hullabaloo had begun, had to attend all the weddings in order that there be a minyan.

4. The Hullabaloo Grows.

And when it became day, there was already an augmentation of eighty new households. Eighty tallis-wearers came to the small synagogues and study houses, and from that day on people stopped saying takhnun (the supplicatory prayer) until the eve of Rosh Hashanah.

People were keeping company in the streets, wandering around half asleep because in every house they were keeping late hours; one can't sleep oneself, and one can't allow others to sleep, because there had to be a minyan at the weddings. Nattering clusters stood near every house, everybody saying Mazl Tov to everybody else in the street.

After prayers, there was a tremendous puffing on pipes in the small synagoges, there was talk and more talk about the weddings. Some held it to be a great idea that came from the big meeting, permitting the previous night's weddings, and they considered it simply a miracle that they'd pulled it off in time, because they'd heard the edict had already reached Byelorussia and people there were already fasting.

Others, on the contrary, were mocking the whole affair. First, they absolutely did not believe such an edict was on its way, and second, they figured that even if it did come, it wouldn't be such a big problem. Those of this opinion, however, were very few in number and were soon shouted down and called heretics. It soon ended in blows.

Aruond ten in the morning, an important regional matchmaker arrived in town with a big noise, because he had a letter from "other parts" that said a maiden would be forbidden to marry before the age of 25 and a young man, under 30. He was so busy, he prayed by himself at the tavern and didn't even want to drop in on a few rich men who'd sent invitations to him a few times - sheerly out of kindness.

"I don't have a spare minute now," he answered their messengers. "Don't you see? The world is in flames, it burns. For me, every minute is gold."

The regional matchmaker's pronouncement instantly spread across town and everyone, big and small, gathered around the tavern where he was staying, to see him in his good luck. Just as a plague of cholera is good luck for a funeral director, just so was this 'hullabaloo' good luck for matchmakers.

Too, it seemed to everyone that he'd bring along behind him a pack of matchmakers. Some of the rich women started wagging their tongues, hoping to get in at least a word with him. However, it was as impossible to approach him as to approach a great rabbii.

He was just barely willing to see one of the richest men, Reb Elyokim, to pause near his house as he was passing by - he wouldn't even go inside, the rich man had to go out to him in order to consult with him, standing, about a matter, probably about his 12-year-old girl.

"Obey me and do it!" people heard the matchmaker shout at Reb Elyokim. "Obey me, again I say, and do it. Now is not the time for trifling about and being choosy. The world is burning!"

And he left by postal coach. That was demonstration enough for the people of Herres that things were not simple in the world. That a matchmaker wouldn't enter Reb Elyokim's house, and further, that he would travel by post!

And that afternoon the hullabaloo began to advance, hour by hour. It was seen that those who in the morning were full of ridicule were by evening leading their children to the khuppah.

And those people who had first been swept up in the furor the previous evening, and who were of a better station in life, made their weddings in the synagogue courtyard, with ritual clown and musicians, or that is to say, with one fiddler alone, or just a tsimbl player. In a pinch, even just a drummer was sufficient.

The badkhn (clown) had no time to attend more than the service.

On the second night there were even more weddings than on the first, and the town was in a commotion/uproar.

5. The Villagers

The aforementioned bitter tidings had by the third day spread through the surrounding villages with a thousand times greater terror. The village folk began to hear that people had only eighteen days in which to marry off their daughters (and boys, just 30 days). And that for divorced women and widows, it was too late already, and that a divorced man or widower was forbidden to marry a fifth time.

Nu, so they became so very confused, and they threw down the sickles from their hands (it was harvest time just then) and they hitched their horses to the empty rackwagons and rode into town by the hundreds, and they stopped with their wagons in the market square because there was no other place they could all turn in at once.

And before they had time to climb down from the rackwagons and ask if what they'd heard was true, they quickly heard the klezmers playing and saw so many brides and bridegrooms being carried from every little street to the synagogue courtyard, that they understoon everything they'd heard was indeed true and so didn't even bother to ask. They just fell in among the townspeople asking for help in finding brides and bridegrooms.

So the little synagogues and poor children's schools were opened for them, and the poor orphans were driven together, that used to go begging between the houses, and the townspeople sold them to the villagers for a pretty penny.

6. The Rich Folk

And so the hullabaloo advanced from day to day. There were weddings upon weddings, no end in sight, not to mention engagement parties.

And really there were only twenty or thirty families in town who remained indifferent and who hadn't been swept up in the crisis. These were the rich folks, big businessmen, who were neither pious old-style Jews nor Khasids. They prayed sometimes here, sometimes there, wherever was convenient. They'd had little intercourse with the townspeople, they were rarely home. Furthermore, they'd been born in big cities and had come here as sons-in-law, were now already divorced or widowed, and for a couple of weeks had been laughing about the big to-do.

"No," they said, "we don't believe the letter Berl received from his father-in-law in 'other parts.' Now, it certainly could be that that inlaw didn't have the money to pay a gift for his son, and hence wrote the letter so he himself could make a wedding.

"We also don't believe the matchmakers, because they're getting a whole festival/market day out of this. They've made a whole business out of it and told 8,000 lies."

However, their authority/credibility in this matter didn't last even two weeks; their wives didn't rest or let up, they bothered their ears saying they were not smarter than the rest of the world, especially not while more daughters had fallen upon them than upon others. Furthermore, the rav had explained to them that as they separate themselves from the community, this in itself can damage/harm prospects of future matches.

And who could say? Perhaps that regional matchmaker was right? Then one really wouldn't be able to show oneself before God and the community.

And besides all this, their daughters really began to worry like Lot's daughters, that their wouldn't be any bridegrooms left for them, that all the boys would be taken.

In short, the rich men were attacked from all sides, until they had to give in and be swept away in the stream of the crisis.

However, in order to distinguish their weddings from the panic-weddings which were being put together like children's games, the rich men let it cost them a few dozen rubles in bribes to the assessor, to induce him to let their weddings take place publicly, as is appropriate. They thought the assessor perhaps had received an order on the subject. But the assessor, who didn't know anything about anything, let them go ahead and knock themselves out (literally, go head over heels, turn somersaults!).

And so that things might proceed in better order, they hired four poor boys to hold up the poles of the khupa more than 24 hours a day, and the two kinds of musicians in town divided themselves into two groups, one to stand under the khupa and play, the other to bring the bride and bridegroom to the wedding and then play them home again.

And there was a congestion/traffic jam/throng near the khupa, just as around the cantor during the Days of Awe, and all sorts of inlaws would be waiting with the greatest impatience for other inlaws, who were already under the khupa, to leave.

7. The Cantor

It was also a golden time for the cantor, because he was raking in the dough. He sat the whole time in the vestibule with his choirboys. He ate there, slept there, wrote the marriage contracts there (the pen belongs to/pertains to the cantor). And the whole time he'd be sticking his head out and singing "Mi Adir..."

His wife was also there, sellign wedding rings, packets of prayer shawls, glasses for breaking. And it was there that, during the short breaks he had available between one wedding and the next, he would also dispatch the beasts and kill chickens and small animals, since he was also the town's ritual slaughterer.

And it was there that he led the children to the slaughter along with the cows and hens.

Nu, for wedding singing he used to charge twice what it cost for killing a baby goat - because under the khupa there was a double act of slaughter. And this is also perhaps the reason why a khupa has four poles while a stretcher for the dead has only two - because there, under a khupa during the turmoil-time, two were buried, while after the washing of a corpse, just one.

At that time, people didn't do any learning at any of the study houses because every day everyone was attending some inlaws' affair. Those who had no children were also inlaws throughout the turmoil-time, because they used to take pains to seek out, from under the ground, any sort of hardship cases, a cripple, a hunchback, and get them married off.

Rightly did a certain German once say perceptively: "A Christian, when he has a lot of children, makes one wedding. A Jew, when he has one child, makes a few weddings. If he has absolutely no children at all, he makes a hundred weddings."

8. The Crisis kicks it up a notch

And the turmoil advanced from day to day, so widely that the whole town looked like a wedding depot. Even people who were just passing through got married. Should a boy or girl enter the town, before they got to the other side they'd already been made a householder or housewife. The town walls closed in on them, were locked and not let open until they'd gotten hitched.

In short, all classes of people had fallen prey to the panic, poor and rich alike. Lots of children went under the khupa completely without their parents' knowledge. A lot of serving maids, sent to the market for barley groats and flour, came back as wives or didn't come back at all. Plenty of little girls who didn't already have little boys to marry were given to old widowers who were thinking more about the World to Come than about this one.

Plenty of men dragged their brides to the khupa by the hand. Many were attacked/assaulted by the Turmoil unexpectedly and, let it not happen to us, were married off most suddenly.

Here, I just talked half an hour ago with someone who'd gone out to buy buckwheat cakes, a dwarf in his forties, furthermore an asthmatic with a hernia, no thought at all of marrying, all the more so because he'd already divorced two wives. He'd been carrying his buckwheat cakes along, just when the town should have been peaceful and quiet, when all of a sudden, half an hour later, as I live and breathe, he was already standing under the khupa and the cantor was already singing "Mi Adir" over him.

In short, not even a child in a cradle was safe from the panic. For a span of four weeks you didn't see a boy or girl on the streets, just as you don't see a white rooster the day after Yom Kippur.

Prayer shawls were running out, so people cut them in half. Men who died during this period were not buried with prayer shawls because the rav said: "A bridegroom takes precedence over a corpse."

Meanwhile the town didn't give a thought to earning a living. The stores were closed. The people went around in their holiday best and as soon as two people recognized each other they said Mazl Tov! not knowing at all if there'd been a wedding - but then, who hadn't been making a wedding at that time?

9. Two Brothers

And it came to pass, in the days of the hullabaloo, that neither equality of age nor pedigree were taken into account, whereas in previous times folks didn't allow even the slightest detail of their ancestry to be overlooked. People used to set up matches the way you set up a booth on the eve of Succot. But now, a ten year old boy might be put together with an 18-year-old girl and the reverse as well, a ten year old maiden with a young widower.

So it happened that a certain father had two boys, one nine years old and the other seven. The elder was married to an eighteen year old girl, because a younger one couldn't be found, they'd already been snatched up.

Understand, such an engagement couldn't hold up, it was like hitching a silk strand to a coarse rope. With time, that 'man-and-wife' business was such a burden to the nine-year-old that when evening came along he used to hide. He'd creep into a mouse-hole so he wouldn't be coerced into being with such a person who'd embittered his life rather than sweetened it.

It happened that his father beat him a few times, and he began to cry and shouted: "Why do you force me over there? Let Yoshke go today!" (That was his younger brother.)

10. The Sabbaths

Every Sabbath people used to bring a transport of householders to shul, big and small, in little shreds of prayer shawls. They'd go up to the Torah in groups of three or four, as on Simkhas Torah, all at once. The little householders brought slices of challah and chicken drumsticks with them, and they'd eat during the reading of the torah, standing on a bench, hair full of the barley women had poured over them while they'd been bedecking the bride that week... there was no talk of combs around those parts for a whole year, especially during the Panic, when things were simply falling out of people's hands.

The new housewives brought their dolls and their jacks to the women's section of the synagogue, and during the day they poured sand into their veils. On Shabbos morning, after prayers, the newlyweds would go around wishing everyone Good Shabbos, and, well, on Sabbath the whole town went wandering about, and inlaws were met up with, some back from reading the Torah at shul, others returning from the morning entertainments that follow a wedding.

Furthermore, inlaws were driving in from many other towns, and so were loads of matchmakers. In the evening there were celebration feasts, at night Sabbath songs sprang up. Briefly, in those days of the Panic people didn't sleep, didn't eat, didn't work, didn't study. They just drank and made weddigns.

11. The end

The panic went on for a full six weeks and would have endured longer if there had been four boys left to hold up the khupa poles. The whole town had been so hornswoggled (the wool pulled over their eyes, literally "veiled") that not one servant girl was left to any household - they'd all married and become, themselves, housewives without servants.

No shoemaker or tailor was open for business because at that time, all commerce and tradework had stopped.

And then, a few weeks later, when the official edict arrived, saying no maiden under sixteen nor boy under eighteen could marry, there were a whole lot of divorces. It was then that the people looked around, seeing how foolish they'd been, and were embarrassed in front of each other.

There were divorces upon divorces. The rabbi's court tried case after case.

A few months later there were twice as many serving maids as before.

Nine months later there were a lot of wet nurses, as in Egypt during the time of the evil decree when the boys had been thrown in the water.

And after that, there remained many deserted wives (grass widows); a lot of men had wandered away into the world and thrown away their wives.

A few of my daughter

Melina's great posts:

A few of my daughter

Melina's great posts: