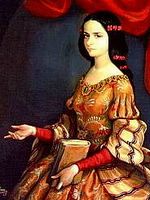

From Mexico: The rebel nun of the 17th century

That title was given to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Las Mujeres. What a great story!

Sor Juana was born Juana Ramirez de Asbaje in 1648 -- or 1651 -- to a Spaniard who abandoned the family and a creole, illiterate as were virtually all women at that time, who managed her father's hacienda outside Mexico City and had six children probably without ever marrying.

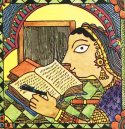

Juana learned to read and write at the age of three.

"I remember that in those days, though I was as greedy for treats as children usually are at that age, I would abstain from eating cheese, because I heard tell that it made people stupid, and the desire to learn was stronger for me than the desire to eat."At eight she composed her first dramatic poem, in honor of the Blessed Sacrament. After reading every book in her grandfather's big library, she tried to persuade her mother to let her go to university dressed as a man (since only men could go). That was nixed, but she was allowed to go live with family in Mexico City where she astonished her priest by mastering Latin in 20 lessons, though even that seemed too slow to her so she punished herself by cutting off her hair:

"It turned out that the hair grew quickly and I learned slowly. As a result, I cut off the hair in punishment for my head's ignorance, for it didn't seem right to me that a head so naked of knowledge should be dressed up with hair. For knowledge is a more desirable adornment."

In 1664 a viceroy and his wife, newly arrived in town, heard of Juana; smitten by her beauty and learning, they took her as a maid-in-waiting and Juana spent some years at their court, studying and writing poetry. The Marquis periodically tested Juana's brilliance with rooms full of theologians, philosophers, mathematicians, historians, poets, and other big brains; she answered their questions and argued her points with ease.

In 1664 a viceroy and his wife, newly arrived in town, heard of Juana; smitten by her beauty and learning, they took her as a maid-in-waiting and Juana spent some years at their court, studying and writing poetry. The Marquis periodically tested Juana's brilliance with rooms full of theologians, philosophers, mathematicians, historians, poets, and other big brains; she answered their questions and argued her points with ease.Juana decided to enter a convent:

"Given my complete aversion to marriage, this was the most seemly and decent choice I could make, for the security I wished and for my salvation ... wanting to live alone, not wanting to have an obligatory occupation that would hamper my study, nor the sounds of a community to intrude upon the peaceful silence of my books."She joined the Carmelites at 16 but soon left; two years later, she entered the Convent of the Sisters of Saint Hieronymus (San Jerónimo) and remained till her death, as treasurer, archivist, and secretary, but primarily as a scholar.

Her convent cell, rather luxurious with its several bedrooms, sitting room, kitchen, study, and bathroom with tub and hot water, became "the intellectual center of Mexico City" (more). Sor Juana's "cell" was large enough for her, her servants, and an extra girl or two living there for education and safekeeping. Despite vows of poverty, the nuns had books and jewelry and bought and sold property and investments.

Her convent cell, rather luxurious with its several bedrooms, sitting room, kitchen, study, and bathroom with tub and hot water, became "the intellectual center of Mexico City" (more). Sor Juana's "cell" was large enough for her, her servants, and an extra girl or two living there for education and safekeeping. Despite vows of poverty, the nuns had books and jewelry and bought and sold property and investments.Sor Juana's library of several thousand volumes was the largest in Mexico if not all of America; she had musical instruments and scientific apparatus including a telescope.

The rule prohibiting visitors and contact with the outside world was widely ignored. The convent locutorium was essentially a literary salon; Sor Juana received and entertained the Marquis and his powerful friends, famous writers and scholars, local and foreign guests who made virtual pilgrimages to be in the same room with her. She corresponded with scientists, philosophers, and powerful people all over the world. In Spain she was called "The Tenth Muse."

Sor Juana composed songs for productions that were attended by members of the court. She is mainly famous today for her poetry and prose on secular and religious themes: loas, plays, comedies, historical vignettes and imaginative tales of mythology. This is how I heard of her - my son is studying her poetry in his AP Spanish class!

When Sor Juana's royal protectors eventually departed, she was left vulnerable to intensifying clerical disapproval of her writing and studies. In response to one attack she penned an autobiographical "Respuesta" in 1690:

Oh, how much harm would be avoided in our country if older women were as learned as Laeta and knew how to teach in the way Saint Paul and my Father Saint Jerome direct!The golden years had come to an end: Sor Juana's books, musical instruments, scientific equipment and other possessions were suppressed or confiscated. She wrote no more for the public and died in 1695 caring for plague-stricken sisters in her convent.

... if fathers wish to educate their daughters beyond what is customary, for want of trained older women and on account of the extreme negligence which has become women's sad lot, since well-educated older women are unavailable, they are obliged to bring in men teachers to give instruction ...

... many fathers prefer leaving their daughters in a barbaric, uncivilized state ...

... ever since the light of reason first dawned in me, my inclination to letters was marked by such passion and vehemence that neither the reprimands of others (for I have received many) nor reflections of my own (there have been more than a few) have sufficed to make me abandon my pursuit of this native impulse that God Himself bestowed on me.

He knows that I have prayed that he snuff out the light of my intellect, leaving only enough to keep His Law. ... I have attempted to entomb my intellect together with my name

I thought I was fleeing myself, but---woe is me!---I brought myself with me, and brought my greatest enemy in my inclination to study, which I know not whether to take as a Heaven-sent favor or as a punishment. For when snuffed out or hindered with every exercise known to Religion, it exploded like gun-powder; and in my case the saying "Privation gives rise to appetite" was proven true.

In her time, Sor Juana was known as the Mexican Phoenix, "her work rising as a flame from the ashes of religious disapproval" (more). For twenty-six years she wrote sonnets, romances, comedies, plays, music, farces, and more; she is considered the last great author of Spain's Golden Age.

Scientists praise her investigations of natural phenomena, her reading of all scientific texts she could get her hands on, and her dialog with scientists in Europe; philosophers laud her insatiable desire to understand everything around her, her studies in classical and medieval philosophy, and her fierce believe in a woman's right to participate in scholastic inquiry.

Sor Juana's "influence helped create a Mexican identity, contributing to the consciousness and sensibility of later scholars and writers" and today she is known as the intellectual mother of Mexico (more).

Dartmouth has digitized many of her works and they are searchable online.

Technorati Tags: History, Women, Mexico, Nuns, Writing

A few of my daughter

Melina's great posts:

A few of my daughter

Melina's great posts:

3 Comments:

I used to tutor a Spanish woman. She'd learned her English in Norway and came to me when the Filipinos started critiquing her English. I asked her to tell me about Lope de Vega, a contemporary of Shakespeare and Marlowe whose literary output far exceeded theirs. He wrote more than two thousand plays. Shakespeare wrote less than fifty. Marlowe died before he got to two digits. But Shakespeare's women, I'm told, were a lot more interesting than Lope de Vega's. I wouldn't know. The plays still haven't been translated.

Dear Craig (and Melinama if interested),

Au contraire. At least one of Lope's play's has been translated. It is called "Fuente Ovejuna" ("Sheep's Well" is one of the English titles I've heard. The name is something along the lines of a well or a fountain of sheep or lambs) and is set in a town of the same name. It's been a while since I read or saw it, but I remember a very strong heroine (albeit, there weren't many strong people of either sex in that piece) who rallied the town to rise up against the 'Comendador' (a mayor of sorts, very much in the style of Robin Hood's Sheriff of Nottingham) after he raped her on her wedding day (to someone else - can't remember the name of the old custom where the nobles are 'entitled' to deflower peasant brides on their wedding day). There's at least one play about Lope himself, but I doubt it's been published (did a brief table reading of it in Queens a few years back. Wouldn't be surprised if there were others though). Are you looking for Spanish authors? He's not really the same style as Sor Juana.

Happy reading,

Margarita

For anyone who is interested there is a movie called "yo, la peor de todas" about Sor Juana's life although there are some aspects of her life portrayed differently. I just learned about her in my Latin American literature class--she is one of the biggest and most recognized feminists in history!

Post a Comment

<< Home