I'm working on this for Scott Davis, proprietor of

JewishStoryTeller.com and author of "Souls are Flying," with the sage counsel of Musia Lakin.

My son Zed read part one and part two and said "this is some shaggy dog story!"

In

part one and

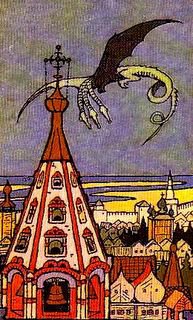

part two, Tevye - at the time a bitterly poor man who supports his wife and many daughters by dragging logs to town and selling them - is making his weary way home one evening when he comes upon two rich ladies lost in the woods. They nag him into turning his wagon back towards Boyberik (it's like a fancy gated community) and taking them to their

dacha (fancy country home). On the way he talks to himself, wondering if he can make a little money from his kind act.

The Big Windfall, (A Groyse Gevins) part three

Sholom AleichemGod sent you this encounter, such as comes along once in a hundred years, how could you not have settled on a price right at the start, then you'd know what you're getting out of this!

Whether you're talking about justice, or common sense, if it's from the point of view of simple humanity, or of Yiddish law or Russian law -- or even from the point of view of I don't know what -- well, is it a sin if you lick the chicken bone, pluck the fruit that's right in front of you? Here's your chance: stop the horse, you cow, tell them this and that, say it straight out: "I get exactly so much and so much from you, everything's fine, but if not - I ask you, get down from the wagon!"

Only then I say to myself again, "You're such a cow, Tevye! You don't know. One can't sell the pelt off a bear in the woods [because the bear is still wearing it i.e. there's many a slip twixt the cup and the lip], or as the goys say: 'You haven't caught the bird yet but you're already plucking it.' "

"Why don't we travel a little quicker?" say the women and they nudge me from behind.

"How is it that you're so short of time? Nothing good," I say, "comes from hurrying!" I take a sidelong look at my little characters: seemingly, women, the usual kind, one with a silk kerchief, the other with a wig, sitting and looking at each other and whispering together.

"Is it much farther?" they ask me.

"Are we almost there? Definitely not," I say. "Here, soon," I say, "we go down a hill, then up a hill, after that," I say, "we go again down a hill and up a hill and right after that," I say, "we have a steep uphill, and from there the road goes straight, straight to Boiberik."

"What a shlimazl," one calls to the other.

"The nightmare just drags on," says the other.

"It's the last straw!" says the first again.

"He's crazy," says the other.

"Exactly," I think to myself, "as usual, I'm a crazy man, that I let these women lead me by the nose."

"Where, for example, will you be wanting me to throw you off the wagon, my dear women?" I call to them.

"What?! Throw us off?! What's that mean?" they say.

"Coachmen speak this way," I say. "In our language we'd say, rather: 'In what vicinity would you bid me have you disembark, should we come,' " I say, " 'to Boyberik, with the Supreme One's aid, healthy and strong, if God will kindly give us the gift of life?' As they say: 'Better to ask [directions] twice rather than to get lost once.' "

"Oh, that's what you mean? You can be so good as to let us off at the green dacha by the river, on the other side of the woods. Do you know where it is?"

"Why wouldn't I know?" I say. "I know Boyberik as well as I know my own home. I should only have 2,000 dollars for all the logs I've carried here. Just recently, the summer before last," I say, "I set two large bundles of wood against that green dacha. A really rich guy lived there, from Yehupetz, a millionare-chik, with at least a thousand karbn (unit of money) and maybe two thousand."

"He's living there still!" both women call to me and look at each other, whispering and laughing.

"Sha," I say, " 'if the trouble from carrying is so great' - if it can really be that you have some kind of connection with him, would it perhaps be," I say, "it probably wouldn't be a bad idea to favor me, have a little talk with him for my sake, a favor for me, a job, some position, I don't know what.

"I know," I say, "a young man, his name is Israel, he was a nobody with nothing; he got himself to Boyberik, nobody knows how. And to make a long story short, now he's a V.I.P., now he earns maybe 20 karbn a week, maybe as much as forty, who knows! Some people have the luck! You know, for example, what happened with our shochet's son-in-law? What would have happened to him, if he hadn't gone away to Yehupetz? True, the first few years he was ground down, he almost starved to death. But then - no harm to him, I wish it would happen to me - he's already sending money home. He already has a mind to take his wife and kids away from here. But he himself isn't allowed to stay there [he's too low class], ay, that's really the question: where DOES he stay? He really tortures himself - a pity, I say. Live long enough, anything can happen...

"Here you have," I say, "the river, and here's the big dacha," and I drive right in as though I belong there, in a rage, straight into the courtyard.

As soon as we were spotted there was an outcry, a clamor: "Oy, Grandma! Mom! Auntie! You found the way home! Mazel tov! Gevald, where were you? We were out of our heads all day! We sent messengers into the woods. We thought it was something from a story, maybe wolves? Robbers, God forbid? What's the story?"

"The story's a fine one: wander in the woods, get thoroughly lost, wander so very far, maybe ten versts. Suddenly a Jew... what kind of Jew? A shlimazl with a horse and wagon... we could barely prevail on him to help us in our troubles..."

"That's terrible, what a dismal nightmare; alone, wholly without a protector? What a story, what a story, thank God 'for he hath brought you through danger.' "

So, in brief, they brought lamps out into the courtyard, prepared the table, and began bringing hot samovars full of oceans of tea, with sugar, with jam, with good pastries, with fresh butter-rolls, good smelling, all kinds of comestibles, the most expensive delights, rich broths and finely cooked things, lots of goose, with the best wine, cherry and plum shnaps.

I was standing some distance away, and I thought - no evil eye - how the rich folk of Yehupetz - no evil eye - eat and drink. I'm just a pawn passed over. I thought to myself, "one should be a rich man!" It seemed to me that what fell off the table onto the ground around here would be enough to feed my children for a whole week, until Shabbos.

"Dear God, gevald, dear Friend, You are really a big God and a good God, a God of loving-kindness and justice, how is it that You give away to one man everything, to the other absolutely nothing? For one, butter-rolls, for the other, a plague on the first-born son?"

But then on the other hand I thought to myself: "You're a big idiot, Tevye, I swear! How is this relevant? You want maybe to dictate to Him how to manage the world? Maybe, if He makes it this way, it should be this way. It's a sign for you - when things

should be different, they

will be different.

"Ay, what? But really, why

shouldn't things be different? Is the reason 'we were slaves' - is that why we are such little bits of Jews in the world? A Jew should live with hope and faith; he should believe, first, that there is a God here in the world, and we should find hope in Him, who lives forever, that things will, maybe, if He wills it, get better."

"Sha, where is that Jew?" I hear somebody say, "has that shlimazl already ridden away?"

"God forbid," I call from a ways off. "What do you think, that I'll ride off that way, without a goodbye? Good evening to you, 'shalom aleichem,' 'blessed are those who are already sitting where they live and having a nice meal,' eat healthy, you're welcome to it."

"Come here!" they say to me, "Why are you standing there in the dark? Let's look at you at least, to see what kind of face you have. Maybe you'd like to take a bit of brandy?"

"A little brandy? Oy," I say, "who would turn that down? How does it go in the book? As Rashi says: 'God is God and brandy is brandy.' L'chaim!" I say, and toss down a cup. "Let God give," I say, "and may you always be rich and have great satisfaction. May Jews," I say, "always be Jews! May God give them," I say, "health and strength, such that they shall be able to overcome misfortune."

"What are your names," the rich man himself (a good-looking Jew in a skullcap) calls to me in lousy Hebrew. "Where are you from? Where do you live? What's your occupation? Are you married? Do you have children? How many?"

"Children?" I say, "One can't complain. If each child," I say, "would only be, as my Goldie says, a million bucks, well I'd be richer than the richest guy in Yehupetz. The problem," I say, "is that poor isn't rich, crooked isn't straight, as the book says: 'that which separates the sacred from the profane,' the one that's got the dough is the happy one.

"Actually it's Brodsky who has the dough and I who have the daughters. And if one has daughters, forget laughter, oh well, never mind, God himself is also a father. 'He carries out,' that's to say he lives above and we toil away here below.

"One slaves, one drags logs, does one have any choice? As the Gemarah says: 'if there is no mentsh then you must be the mentsh.' Is a herring fish? The whole misfortune is - one must eat. As my granny, rest her soul, used to say, 'when the mouth lies in the dirt, the head goes in gold.' If only we didn't have to eat, we'd be rich. Don't be offended," I say, "nothing straight comes from a crooked ladder and nothing crooked comes from straight talk, especially," I say, "on an empty stomach."

"Give the Jew something to eat," the rich man called - and there, created on the table, a feast, 'of all the kinds of fish and flesh,' fish, meat, nicely made things, and chicken quarters, and gizzards and liver without end.

"Would you like something to eat?" they ask. "Go, wash up!" "You have to ask a sick man if he wants to eat, but don't ask a healthy man -- just give him the food."

on to part four ... Technorati Tags: yiddish, sholom+aleichemLabels: yiddish

A few of my daughter

Melina's great posts:

A few of my daughter

Melina's great posts: